Changing global dynamics benefit 'inbetweener' economies

If there were any lingering uncertainties, the unipolar U.S. era has ended. On January 30, newly appointed U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced the end of the nation’s thirty-year dominance as the exclusive judge of global matters, referring to it as an “anomaly.” Two weeks later, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth articulated, opens new tab distinctly the emerging situation when he referred to China as a “peer competitor” and informed fellow NATO allies that the U.S. must from now on prioritize deterring its new superpower adversary. Russia’s attack on Ukraine, the wars in the Middle East, and the U.S. pressure on allies from Canada to Panama to resist what it describes as Chinese infiltration were already indicators of a novel, essentially bipolar global order. President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs on international trade partners, announced on Wednesday, highlight the ongoing change.

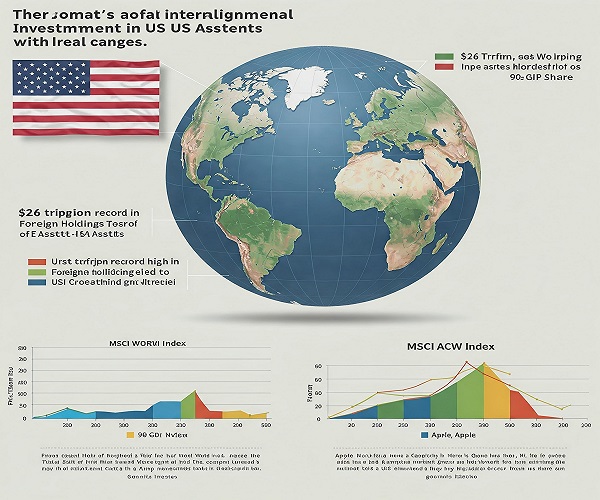

International investment distributions, however, continue to be strikingly misaligned with this monumental geopolitical change. For the last fifteen years, U.S. capital markets have been the sole option available. In December, net foreign holdings of U.S. assets reached a record high of slightly more than $26 trillion, nearly 90% of the United States’ GDP, as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The U.S. stock market is enormous – and highly valued – as it represents nearly three-quarters of the MSCI World Index, which includes developed market equities. Three firms – Apple (AAPL.O), opens new tab, Nvidia (NVDA.O), opens new tab, and Microsoft (MSFT.O), opens new tab – collectively account for larger portions of the MSCI ACWI Index, opens new tab of global stocks than the whole UK stock market

US commitments to international investors have continued to grow

A line chart showing US net international investment position as % of GDP

A notable type of investment locations could be called “inbetweeners”: significant emerging markets that possess investable financial markets while also having the economic and geopolitical influence to steer clear of complete alignment with either the U.S. or China. Investors will certainly have differing opinions on which jurisdictions fulfill these two criteria. However, at the very least, Brazil, Turkey, South Africa, the Gulf Cooperation Council nations, India, and Indonesia qualify. That group alone renders the inbetweeners too significant to overlook. Together, they represent over a quarter of the world’s working-age population; close to a fifth of global GDP assessed by purchasing power parity; almost a sixth of worldwide active military personnel; and about a tenth of global trade and defense expenditures, respectively

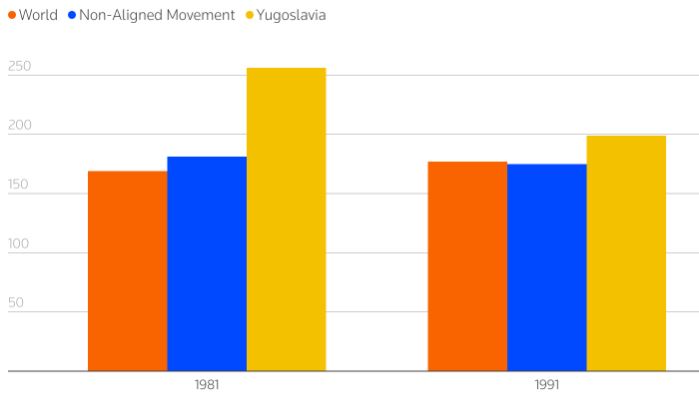

The notion that strategic neutrality can produce concrete economic benefits, in the meantime, has historical examples to support it. In 1961, the heads of 25 developing nations established the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) with the specific aim of maintaining independence in trade, technology, and financial connections with the two superpowers of the Cold War. In the following twenty years, that approach proved successful. Income growth per capita in NAM countries significantly exceeded the global average. Key members who capitalized on the chance to borrow from and trade with both the east and west reaped even greater rewards. Egypt, Yugoslavia, and Indonesia expanded their economies at average yearly rates of 6.0%, 5.7%, and 5.4%, respectively, for two decades continuously

In the current age of more interconnected global trade and capital markets, the advantages of having positive relations with both of the world’s superpowers are certainly greater. To experience the benefits, consider financial centers like Dubai and Singapore – the thriving cities attracting global bankers from London and New York – or previously underdeveloped regions like Kazakhstan that have transformed into lively centers of east-west commerce. Acting as the intermediary in a global economy that is tenfold larger than it was during the era of the initial NAM is at least ten times more valuable. Disregard the regulatory and tax advantages that have been crucial for optimizing corporate capital frameworks and supply chains over the past thirty years. Geopolitical arbitrage will reveal resilience and profitability in the new Cold War – and it is the intermediaries that provide the clear preferred destinations for that service

Although non-alignment benefited the original NAM effectively in the 1960s and 70s, its members’ achievements in the 1980s were not as notable. From 1981 to 1991, the group’s growth in per-capita income started to fall behind that of rivals in the western and eastern blocs. In Yugoslavia, which had experienced the most open trade and finance from both sides, income per person actually decreased. It became apparent that the autonomy gained from being essential to both factions in a divided world could readily transition into policy disorder

That serves as a warning for investors drawn to the current inbetweeners. From 2000 to 2014, Saudi Arabia maintained an average budget surplus of close to 8% of GDP. Over the past ten years, lavish investment initiatives like the $500 billion NEOM development have transformed this into an average yearly shortfall of 6% of GDP. Last month, Turkey’s President Tayyip Erdogan faced significant opposition when Ekrem Imamoglu, his primary challenger, was arrested on allegations of corruption, causing a drastic downturn in the nation’s financial markets. The breakdown of the unipolar world order could imply that crucial external limitations on intermediary governance and public finances might also disappear